With children spending more time in front of screens than ever, parents sometimes try to convince themselves that playing Angry Birds teaches physics, or that assembling outfits on a shopping app like Polyvore fires creativity.

According to a study scheduled for release on Friday, however, less than half the time that children age 2 to 10 spend watching or interacting with electronic screens is with what parents consider “educational” material. Most of that time is from watching television, with mobile devices contributing relatively little educational value.

What is more, the study, by the Joan Ganz Cooney Center, a nonprofit research institute affiliated with the Sesame Workshop, the nonprofit producer of “Sesame Street,” shows that as children spend more time with screens as they get older, they spend less time doing educational activities, with 8- to 10-year-olds spending about half the time with educational content that 2- to 4-year-olds do.

Athena Devlin, a professor of women’s and American studies at St. Francis College in Brooklyn and the mother of two children, said that her son, Elias, a kindergartner, still watched quite a bit of public television, including shows like “Wild Kratts” and “Dino Dan,” and that she has been impressed by the detailed facts he learns.

But her daughter, Laura, a fourth grader, prefers shows like “Jessie” on the Disney Channel or “Total Drama Island” on the Cartoon Network, which Professor Devlin sees as the preteen equivalent of her own addiction to “Scandal.”

“I feel like with the educational content of television, the bottom drops out of it after age 5 or 6,” she said. “It’s a bummer, and I’ve looked out for it.”

She said that when playing games, her daughter liked Wizard101, while both children gravitated toward Fruit Ninja or Clumsy Ninja, whose educational value Professor Devlin does not rate highly.

“It would be nice if they could get pleasure out of something that also taught them something,” she said.

According to the survey, 2- to 4-year-olds spent a little over two hours a day on screen, with one hour and 16 minutes of educational time, while 8- to 10-year-olds spent more than two and a half hours a day on screen, but only 42 minutes was considered educational. The survey was based on interviews with 1,577 parents and conducted online from June 28 to July 24 by GfK, a research company.

The survey allowed parents to assess whether a game or program taught social and emotional skills, as well as cognitive learning related to vocabulary, math or science.

The survey said lower-income families reported that their children spent more time with educational programming on screen than middle-income and higher-income families did. Families earning less than $25,000 said 57 percent of their children’s screen time was educational, while families earning $50,000 to $99,000 said it was 38 percent.

Michael H. Levine, the executive director of the Joan Ganz Cooney Center, said that particularly for the most vulnerable children who might falter in their academic careers, “we need to have a better balance in the way these media are used.”

Vicki Rideout, who wrote the report, said that with teachers seizing on digital media as a new way to ignite children’s interest at school, more needed to be done to ensure that out-of-school screen activities were not only educational but of high quality.

“It’s far too easy for the best stuff only to be available for the kids who already have many opportunities,” said Ms. Rideout, “and to flip into content that has the gloss of education on it, without the substance, for the kids who are in need.”

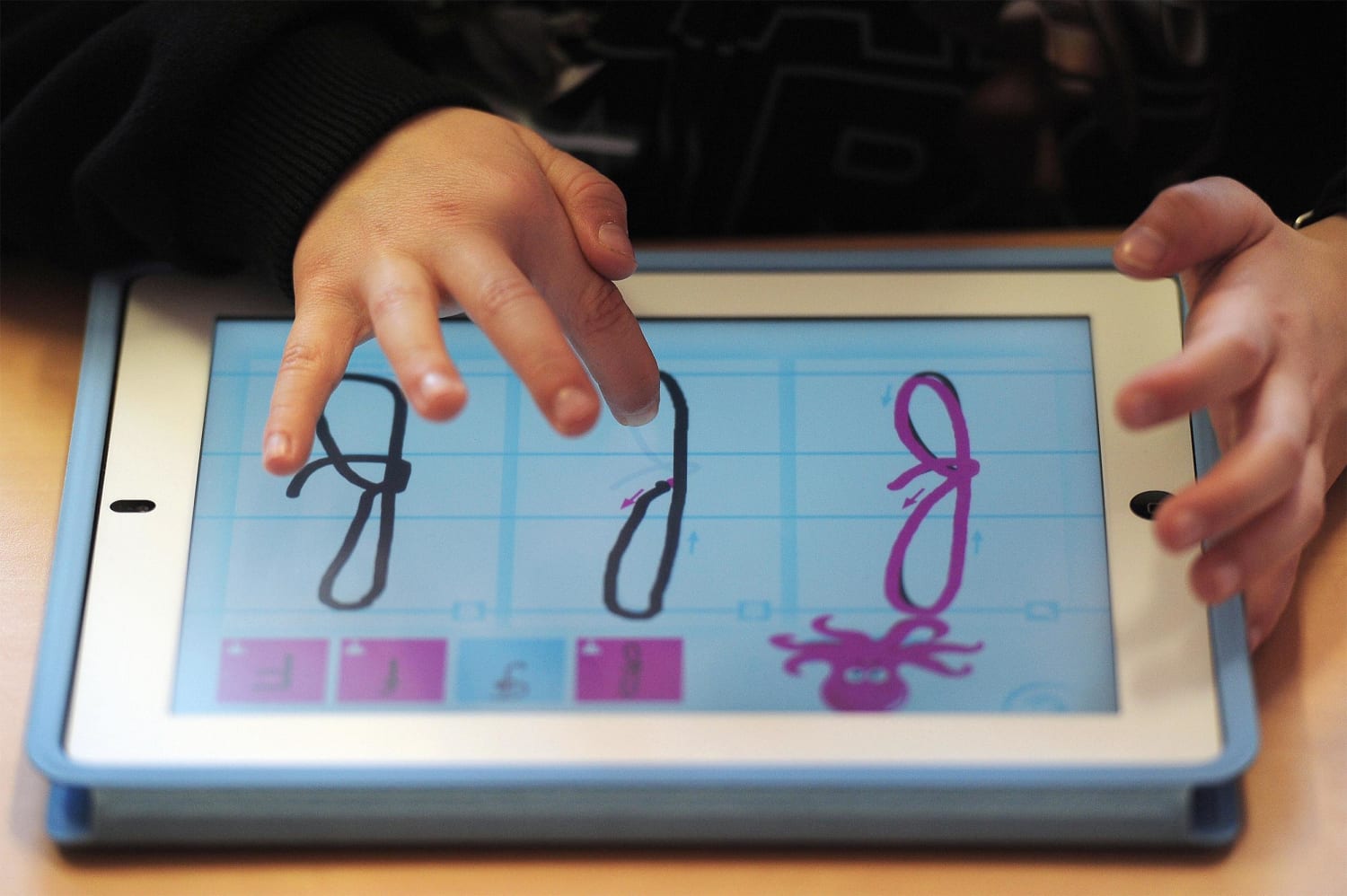

Michael Thornton, a second-grade teacher at Meriwether Lewis Elementary School in Charlottesville, Va., and the father of three children under 6, said parents were increasingly asking him for referrals to educational apps, like Geared and Glass Tower, for teaching math and spatial recognition skills, and Chicktionary, for vocabulary.

But, he acknowledged, “you have to really take your time to search through them.”

Researchers have found that in boys, higher screen time was adversely associated to bone mineral density (BMD) at all sites even when adjusted for specific lifestyle factors.

Researchers have found that in boys, higher screen time was adversely associated to bone mineral density (BMD) at all sites even when adjusted for specific lifestyle factors.