International teams of researchers using advanced gene sequencing technology have uncovered a single genetic mutation responsible for a rare brain disorder that may have stricken families in Turkey for some 400 years.

The discovery of this genetic disorder, reported in two papers in the journal Cell, demonstrates the growing power of new tools to uncover the causes of diseases that previously stumped doctors.

Besides bringing relief to affected families, who can now go through prenatal genetic testing in order to have children without the disorder, the discovery helps lend insight into more common neurodegenerative disorders, such as ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, the researchers said.

The reports come from two independent teams of scientists, one led by researchers at Baylor College of Medicine and the Austrian Academy of Sciences, and the other by Yale University, the University of California, San Diego, and the Academic Medical Center in the Netherlands.

Both focused on families in Eastern Turkey where marriage between close relatives, such as first cousins, is common. Geneticists call these consanguineous marriages.

In this population, the researchers focused specifically on families whose children had unexplained neurological disorders that likely resulted from genetic defects.

Both teams identified a new neurological disorder arising from a single genetic variant called CLP1. Children born with this disorder inherit two defective copies of this gene, which plays a critical role in the health of nerve cells.

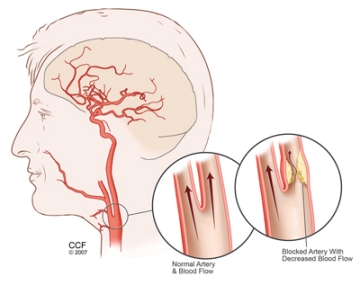

Babies with the disorder have small and malformed brains, they develop progressive muscle weakness, they do not speak and they are increasingly prone to seizures.

Dr Ender Karaca, a post-doctoral associate in the department of molecular and human genetics at Baylor, first encountered the disorder in 2006 and 2007 during his residency training as a clinical geneticist in Turkey.

“We followed them for years,” said Karaca, a lead author on one of the papers. Karaca said he and his colleagues performed some basic genetic tests on the families but to no avail.

He presented these cases at a genetics conference in Istanbul in 2010, where he caught the attention of Dr James Lupski, who leads the Center for Mendelian Genomics at Baylor, a joint program with the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute

The center is focused on finding and recruiting thousands of patients and families with undiagnosed disease likely caused by single-gene defects known as Mendelian disorders.

Lupski recruited Karaca into his program at Baylor, where the team continued to work on identifying more cases. A broad genetic test known as exome sequencing, which looks at all of the protein-making genes representing about 1 percent of the genetic code, eventually identified five families with similar characteristics and the same CLP1 mutation.

Researchers needed confirmation in lab tests that the defect could cause the neurological problems seen in the families. That came at a meeting in Vienna, when Dr Richard Gibbs, director of Baylor’s Human Genome Sequencing Center, presented the gene as part of a list of suspected disease-causing variants.

In the audience was Dr Josef Penninger of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna, whose lab had been working on a model of this same genetic variant in mice.

Both the mice and the people with the genetic defect shared similar characteristics. Further experiments by the Vienna team showed the mutant copies of the CLP1 gene affected the survival of key cells in the brain stem of the mice.

“We had patients with an interesting phenotype (symptoms) and a novel gene but no evidence from the lab that these mutations are disease-causing. They had a model organism, a mouse, but they didn’t have evidence that it affected people. It was a perfect storm,” said Baylor geneticist Dr Wojciech Wiszniewski, author of another study.

As the Baylor-led researchers were working on the problem, collaborators at the Yale Center for Mendelian Genomics, another of the government-funded Centers for Mendelian Genomics, were sequencing families in Turkey under the direction of Dr Murat Gunel, a professor of genetics and neurobiology at Yale.

Gunel and colleague Dr Joseph Gleeson at University of California, San Diego, have been focusing on understanding the fundamental mechanisms of how the human brain develops.

Gunel had been collecting DNA samples from children affected with neurodevelopmental brain problems. The team did exome sequencing on more than 2,000 samples, and they, too, turned up a disorder linked with the CLP1 gene.

Further investigation of the genetic data suggested that all of the cases they identified among four, unrelated families were linked with a single, spontaneous mutation in the CLP1 gene that occurred 16 generations, or about 400 years ago.

Gunel, who received his medical degree in Istanbul, said the high rates of marriages between closely related people in Turkey and the Middle East lead to these rare disorders as affected children inherit mutations in the same gene from both of their parents. Without such marriages, children are very unlikely to inherit two mutations in the same gene.

The Yale paper credits Lupski at Baylor for sharing some of his unpublished findings. Gibbs said the whole effort is an “good example of communication-driven discovery.”

Source: Reuters

Scientists have made a breakthrough in regenerative medicine by fully restoring a degenerated organ in a living animal for the first time.

Scientists have made a breakthrough in regenerative medicine by fully restoring a degenerated organ in a living animal for the first time. Researchers have found that in boys, higher screen time was adversely associated to bone mineral density (BMD) at all sites even when adjusted for specific lifestyle factors.

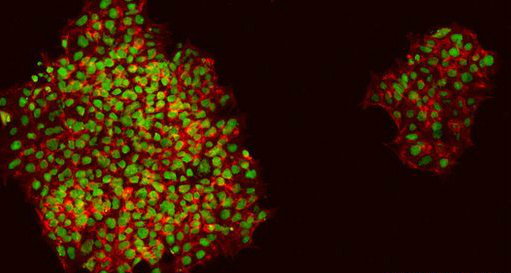

Researchers have found that in boys, higher screen time was adversely associated to bone mineral density (BMD) at all sites even when adjusted for specific lifestyle factors. A new report published in The FASEB Journal may lead the way toward new treatments or a cure for a common cause of blindness (proliferative retinopathies). Specifically, scientists have discovered that the body’s innate immune system does more than help ward off external pathogens. It also helps remove sight-robbing abnormal blood vessels, while leaving healthy cells and tissue intact. This discovery is significant as the retina is part of the central nervous system and its cells cannot be replaced once lost. Identifying ways to leverage the innate immune system to “clean out” abnormal blood vessels in the retina may lead to treatments that could prevent or delay blindness, or restore sight.

A new report published in The FASEB Journal may lead the way toward new treatments or a cure for a common cause of blindness (proliferative retinopathies). Specifically, scientists have discovered that the body’s innate immune system does more than help ward off external pathogens. It also helps remove sight-robbing abnormal blood vessels, while leaving healthy cells and tissue intact. This discovery is significant as the retina is part of the central nervous system and its cells cannot be replaced once lost. Identifying ways to leverage the innate immune system to “clean out” abnormal blood vessels in the retina may lead to treatments that could prevent or delay blindness, or restore sight.