At only 32, Sarah Beth Therien suddenly became unconscious. She was rushed to hospital — and would never wake up. An unexpected heart arrhythmia had left her on life support. “A machine kept her heart pumping, but we knew she was gone,” said Emile Therien, her father.

After a week, Emile Therien and his wife, Beth Therien, made the difficult decision to withdraw life support.

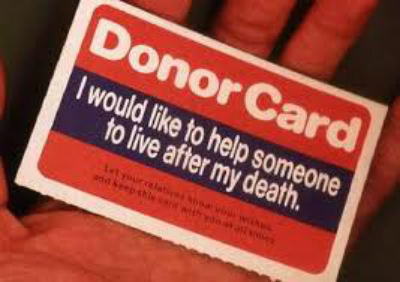

Their daughter had always wanted to donate her organs, but she didn’t meet the brain death criteria required for donation. Her Ottawa family was determined to fulfill her final wish. In 2006, she became the first Canadian in nearly four decades to donate her organs after cardiac death — not brain death. And the decision didn’t go unnoticed.

Six years later in 2012, among the 540 deceased organ donors in Canada nearly 14 per cent donated after cardiac death. Cardiac death donation, also called non-heart-beating donation is now practised in Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, Quebec, and Nova Scotia.

Canada joins other countries like the United Kingdom, United States, Spain, and the Netherlands, where non-heart-beating donation is more widespread.

Donation guidelines revised

Donation after cardiac death was the only method of deceased organ donation prior to the advent of brain death criteria in the 1960s — when the concept of someone being “brain dead” was first introduced. Because the brain dies before the heart, organs taken after brain death aren’t damaged from a lack of blood flow. As a result, donation after brain death replaced cardiac-death donation.

But over the last two decades, organ shortages, improved organ preservation, and public support led to the re-emergence of donation after cardiac death. In Canada, a national forum of transplant experts in 2005 led to the development of new guidelines that paved the way for this type of donation. And made it possible for Sarah Beth Therien to be a donor.

The potential impact is huge. Brain death accounts for only 1.5 per cent of in-hospital deaths. For the majority of patients with non-survivable illness, death occurs as a result of cardiac death after life support is removed.

Donation after cardiac death could increase the number of available organs by 10 to 30 per cent, according to experts. This could mean the difference between life and death for the nearly 4,500 Canadians currently waiting for a transplant, many of whom will die before getting organs.

The most common organs donated after cardiac death are kidneys, followed by livers, lungs, and pancreases.

Success depends on timing of organ removal

The success rate at which potential donors end up donating organs after cardiac death depends on the organs being removed — kidneys last longer than livers after the heart stops, for instance — how long it takes for the patient to actually die, and the person’s blood pressure and oxygen levels during the dying process, Shemie says.

And organs donated after cardiac death may not always work as well as those donated after brain death.

Higher rates of dysfunction have been seen in livers taken after cardiac death, says Dr. William Wall, director of the multi-organ transplant program at London Health Sciences Centre in Ontario. Kidneys donated after cardiac death have trouble working initially, but “one-year functioning is similar for kidneys taken after cardiac versus brain death,” Wall says.

For Emile and Beth Therien, pioneering the process meant a lot. Sarah Beth Therien donated two kidneys and two corneas, changing the lives of four Canadians. Each donor has the potential to save up to eight lives.

“Sarah was able to save other Canadians. Nothing could have made us happier,” Emile Therien says.

Source: CBC