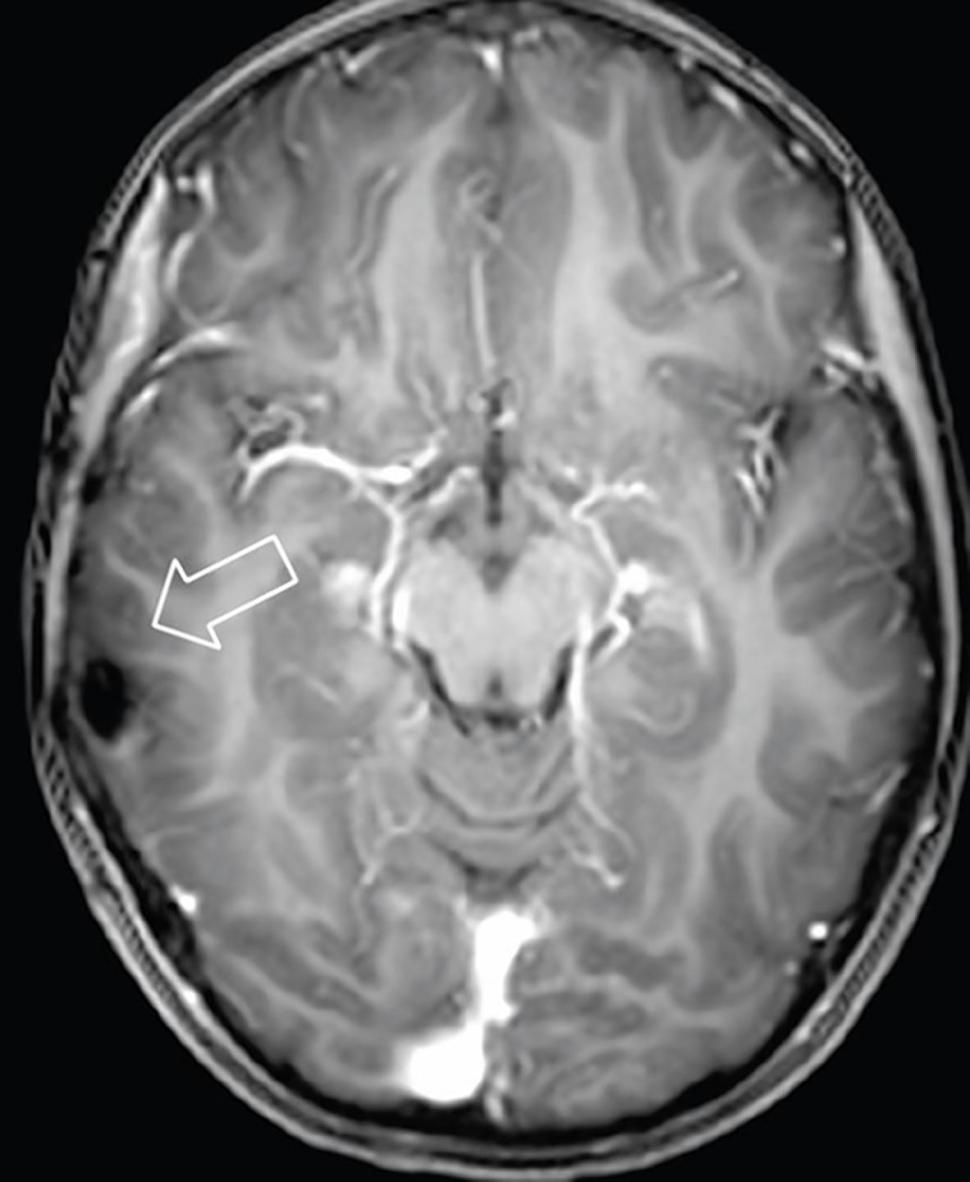

A surgeon operating on a brain tumor does not want to remove any more tissue than is completely necessary. The consequences of removing too much brain matter can be severe.

By the same token, the surgeon is eager to remove the entirety of the cancerous growth; the consequences of leaving a cancerous residue are equally severe.

As things stand, this balancing act can only be managed using the surgeon’s senses. He must palpate the area and inspect it visually for remaining cells.

To fully and definitively ascertain whether a cell is cancerous, a sample must be sent to a pathology lab. There, the sample will be frozen, sliced, stained and mounted. Only then will it be inspected by a microscopist before the results are sent back.

The whole process can take days. A surgeon cannot leave a patient’s skull open to the air for that amount of time, however.

The birth of the mini-microscope

A groundbreaking invention that has the potential to rid us of this waiting game is currently being perfected by the University of Washington. The device, not much bigger than a pen, will allow surgeons to observe their patient on a cellular level, there and then.

This incredible mini-microscope is being developed in collaboration with Stanford University, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and the Barrow Neurological Institute. The ongoing work was recently published in Biomedical Optics Express.

It is not just in the neurosurgeon’s domain that this technological advance might come in useful. Dentists routinely come across a suspicious or unexpected lesion in a patient’s mouth. In these situations, it is important to err on the side of caution, excise the tissue and send it for analysis.

These patients are subjected to procedures that, more often than not, turn out to be unnecessary; this also puts additional pressure on pathology labs.

A miniature microscope could remove the need for many superfluous procedures; in dermatological clinics, for instance, it could be used to quickly define which moles require further investigation.

Source: medica news today