Patients with Parkinson’s disease were less likely to adhere to a Mediterranean-type diet, compared with people without Parkinson’s disease, according to research presented at the 136th Annual Meeting of the American Neurological Association.

The Mediterranean diet—characterized by a high intake of fruits, vegetables, legumes, and olive oil and a low intake of saturated fatty acids—has been linked to a lower risk for other diseases as well. In 2009, Nikolaos Scarmeas, MD, lead investigator of the current study, published research demonstrating that higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet, along with more frequent physical activity, were independently associated with a reduced risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

In the current study, Dr. Scarmeas and a team of investigators led by Roy N. Alcalay, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at the Movement Disorders Division of the Department of Neurology at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City, also found that poorer adherence to the diet was associated with a younger age of Parkinson’s disease onset.

“The interesting question of whether adherence to a Mediterranean-type diet may reduce one’s risk for Parkinson’s disease is unknown,” Dr. Alcalay told Neurology Reviews. “There are many ongoing studies that approach populations at risk for Parkinson’s disease. Considering whether Mediterranean diet adherence reduces their risk for Parkinson’s disease can be very helpful.”

Comparing Patients and Healthy Controls

Dr. Alcalay and colleagues recruited 257 patients (115 women) with Parkinson’s disease and 198 healthy controls (96 women) from three Columbia University and community-based study populations for their case–control study. “Parkinson’s disease participants were younger (68 vs 72) and more educated (14 years vs 12 years) than controls,” the researchers noted.

All participants completed the Willett semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. A Mediterranean-type diet adherence score was calculated using a 9-point scale, with higher scores representing stricter adherence to the diet.

“The Mediterranean diet is characterized by a high intake of vegetables, legumes, fruits, and cereal; a high intake of unsaturated fatty acids (mostly in the form of olive oil) compared with saturated fatty acids; a moderately high intake of fish; a low-to-moderate intake of dairy products, meat, and poultry; and a regular but moderate amount of ethanol, primarily in the form of wine and generally consumed during meals,” Dr. Alcalay noted. Total daily caloric intake for patients with Parkinson’s disease was slightly higher than for controls, and patients’ mean Mediterranean diet score was lower (4.3 vs 4.7).

Source: neurology reviews

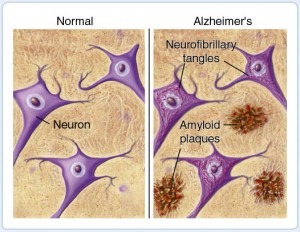

Researchers have identified abnormal expression of genes, resulting from DNA relaxation, that can be detected in the brain and blood of Alzheimer’s patients.

Researchers have identified abnormal expression of genes, resulting from DNA relaxation, that can be detected in the brain and blood of Alzheimer’s patients.