Men burn brown fat for energy only when they’re chilled, researchers have found.

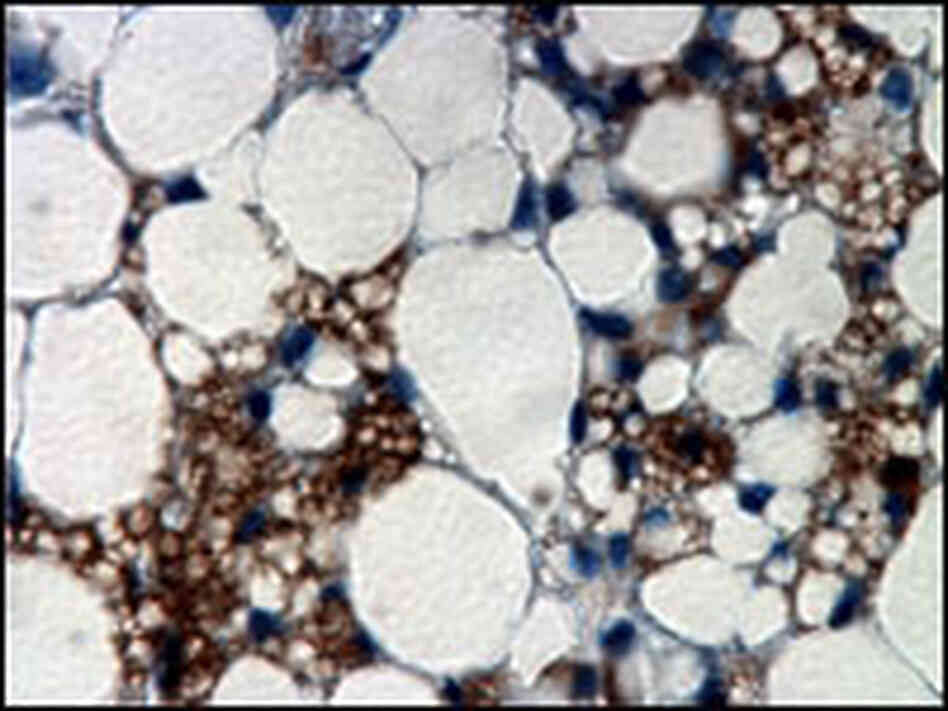

Scientists and drug companies are interested in finding way to increase the amount of brown adipose tissue, also called brown fat, in adults in the hopes of fighting obesity.

They knew that rodents and newborn babies burn calories from brown fat to keep warm. Animals and newborns don’t shiver.

Adults are now known to also carry brown fat, but a big question for obesity researchers was whether that fat actually burns energy.

Scientists in Quebec designed an experiment to find out.

André Carpentier at Sherbrooke University and Denis Richard at Laval University in Quebec City studied six healthy men aged 23 to 42 who wore a water-cooled suit. The experimental set-up was meant to minimize shivering.

When the investigators exposed the men to a radioactive chemical, they found the radioactivity disappeared from the brown fat in just minutes, but the radioactivity wasn’t metabolized in the warm subjects.

Based on the radioactivity findings, the researchers concluded all of the men showed cold-induced activation of brown fat metabolism.

“However, it remains to be demonstrated whether chronic and frequent bouts of cold exposure may contribute to increase [brown fat metabolism] and/or activity and may be a viable adjunct therapeutic strategy to other lifestyle interventions to prevent or treat obesity and its metabolic complications,” they concluded in Tuesday’s issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

In a journal commentary published with the study, Barbara Cannon and Jan Nedergaard at Stockholm University in Sweden said that increasing the amount of brown fat a person has is unlikely to make him or her slimmer. Instead, what’s needed is a way to make that brown fat actively burn calories.

“What we have to wish for is not only more brown adipose tissue in adult humans — but that it would actually be ‘on fire’ when we eat,” the commentators said.

The researchers acknowledged drawbacks of the study. For example, they were unable to tell whether brown fat was metabolically active during cold conditions in other internal organs such as the heart because of the limited view of the PET/CT scanner.

The scientists took body mass index and diabetes into account, but they said the wide differences in brown fat metabolism they observed suggests that other unknown factors could be important, too.

The study was funded by the Canadian Diabetes Association.

Source: Cbc health