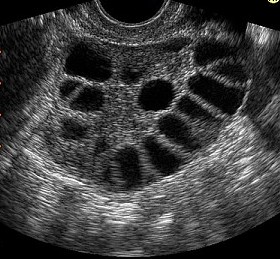

Women with irregular menstrual cycles may have more than double the risk of ovarian cancer compared to women who have regular monthly periods, new research suggests.

This finding suggests that women with irregular periods — including those with a condition called polycystic ovarian syndrome — might be a group that could benefit from early screening for ovarian cancer, said the study’s lead author, Barbara Cohn. She is director of child health and development studies at the Public Health Institute in Berkeley, Calif.

“Ninety percent of women who get ovarian cancer don’t have risk factors for it. Our study findings help to narrow the search,” said Cohn.

“If we can confirm what we have here and can learn more about the mechanism behind ovarian cancer, then we might be able to do something as simple as recommend birth control pills for women with irregular periods, provided they have no other risk factors against birth control pill use,” said Cohn.

However, the study design wasn’t able to show that irregular periods caused ovarian cancer or an increased risk, only that there was an association between the two.

The American Cancer Society estimates that nearly 22,000 American women will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2014, and more than 14,000 will die from the disease. One reason ovarian cancer remains so deadly is there are no reliable early detection tools for it. When found, it’s often in the later stages when treatment is less effective.

Some research has suggested that women who ovulate less frequently may have some protection against ovarian cancer. For example, women who take birth control pills, which prevent ovulation, have a lower risk of ovarian cancer. The new study sought to see if women who naturally have irregular periods, and perhaps ovulate less frequently, had a lower rate of ovarian cancer.

The study included more than 14,000 women who were part of the Kaiser Permanente Health Plan in Alameda, Calif., between 1959 and 1967. The researchers followed the women’s health over the next 50 years or until death. All had at least one child, and none used fertility drugs to conceive, according to the study.

An irregular menstrual cycle was defined as longer than 35 days even if it was regular, a cycle that was unpredictable from month to month (and the woman wasn’t in perimenopause when unpredictable cycles are normal), or if a woman didn’t ovulate, Cohn said. The women were around age 26 when they reported having irregular periods.

Although none of the women was diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome when the study began because the disease wasn’t really recognized at the time, it’s likely that at least some of them had the hormonal disorder, Cohn said.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome is a common cause of irregular periods, but it’s possible that other abnormalities associated with the disorder might also explain the study findings, she said.

During the study, 103 women developed ovarian cancer, 20 of whom had irregular periods, said Cohn. And 65 died of ovarian cancer, 17 with irregular menstrual cycles. The average age of ovarian cancer death was about 69.

Women with irregular periods had a 2.4 times higher risk of ovarian cancer death than women who had normal cycles, the researchers concluded. In addition, women who had a first-degree relative (mother, sister or daughter) with ovarian cancer, a known risk factor for the disease, had almost three times the risk of death from ovarian cancer, said Cohn.

A lot of biological factors increase a person’s risk of ovarian cancer, said Dr. David Fishman, director of the Mount Sinai Ovarian Cancer Risk Assessment Program in New York City.

“This study’s findings are an interesting observation, but it’s not cause and effect, and I don’t want women to be afraid,” Fishman said. “Menstrual irregularities are very common, and most women with menstrual irregularities won’t have ovarian cancer.”

For women who have menstrual irregularities, this study reinforces the benefit of birth control pills to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer, Fishman added.

Any woman who is concerned should talk to her doctor, he said. Her physician can let her know if she’s at an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer. The study findings were scheduled for presentation Wednesday at the American Association for Cancer Research annual meeting in San Diego.

Research presented at medical meetings should be viewed as preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Source; webmd