In 2000, the soaring dot.com industry crashed. Seven years later, the housing boom ended abruptly. With tuition rates swelling, could the medical education market be the next bubble to burst?

Probably not, concludes a paper published Oct. 30 in the New England Journal of Medicine and co-authored by Cornell health economist Sean Nicholson, since such a collapse would occur only if doctors’ incomes dropped sharply and before medical schools could act to rein in costs. However, for veterinarians, optometrists, pharmacists, dentists and certain types of newly minted M.D.s, the prognosis is not so encouraging.

The article, “A Medical Education Bubble Market?,” is co-authored by David A. Asch, M.D. ’84, professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and Marko Vujicic of the American Dental Association.

A bubble market occurs when a good becomes overvalued because buyers are willing to pay higher prices in hopes of selling it for a greater payoff. The bubble deflates when the asset suddenly returns to a more reasonable intrinsic value, leaving buyers from the peak of the boom with something worth far less than what they paid.

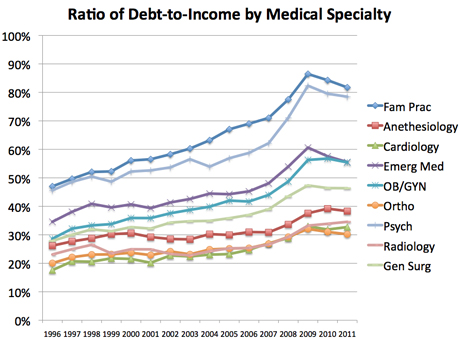

In U.S. health care, medical education costs have risen sharply in recent decades, but medical school slots remain competitive in part because applicants believe their lucrative future wages justify taking on significant debt. But the economics have become much less favorable in the past 15 years, the authors found, based on debt-to-income ratio – the average debt of a graduating student compared to the average annual income of a newly employed physician in that field.

“Debt-to-income ratios reflect what students must borrow rather than what they must pay and, given whatever other assets they may have, how much into the hole they have to go,” the authors write. “Thus, these ratios may better reflect how students actually feel about buying education.”

Family physicians and psychiatrists are the worst off their first year out of school: In 2010, their debt equaled about 85 percent and 80 percent of their yearly income, respectively. That’s roughly double the ratio new doctors in those same fields faced in 1996. Doctors in specialized fields fared much better: Orthopedists, cardiologists and radiologists held a debt-to-income ratio under 35 percent – only a slight rise from 1996 levels.

But the picture is far more troubling for other doctors. The ratio for new veterinarians climbed above 160 percent in 2010, with optometrists (130 percent), pharmacists (110 percent) and dentists (95 percent) not far behind. In fact, veterinary medicine may already be in a bubble market, the authors argue.

As long as physician salaries remain high enough to justify their debt burden, medical education should avoid a similar fate. But, the authors warn, “there are strong signs that we can’t or won’t … keep paying doctors a lot of money.”

The Affordable Care Act is funded largely by reduced Medicare payments to hospitals, part of a growing demand to cut U.S. health care costs. Doctors’ incomes, though sluggish, have been spared so far but could be targeted soon as more savings are sought.

“The main point we are trying to make is the connection between what we as a society are spending on physician services and how much medical schools can charge for tuition,” said Nicholson, professor of policy analysis and management in the College of Human Ecology. “If we are serious about reducing health care spending, then that means we also need to cut the cost of creating new doctors if we want to continue to attract the most promising applicants into the profession.”

The study was funded, in part, by the American Dental Association.

Source; Cornell Chronicle

Nevada’s university leaders have signed a partnership agreement to begin establishing a new M.D.-granting medical school in Southern Nevada.

Nevada’s university leaders have signed a partnership agreement to begin establishing a new M.D.-granting medical school in Southern Nevada.