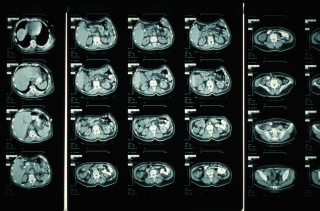

Everyone’s heard a story: Someone got an MRI for a sports injury or dizziness and the radiologist found a tumor, just in the nick of time. Or maybe it was an aneurysm, just about to burst. Lives were saved. It was great luck.

Some of the stories are dramatic. Joan Rachlin of Boston got what seemed to be a routine Pap smear 27 years ago. Like most Pap smears, it was deemed normal. “I got a call something like seven months later from a gynecological pathologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston,” Rachlin told NBC News.

“He was doing research on Pap smear tissue and he had come across mine. He discovered that my Pap smear had been misread and that, in fact, I had a cancerous lesion.”

It’s what’s called an incidental finding — the researcher, who Rachlin says does not wish to be named, was studying something else and in fact had to go to some trouble to match the sample to a real person. “He thought my Pap smear had really been so poorly interpreted that my life was in danger,” said Rachlin, who is executive director of Public Responsibility in Medicine and Research. “I am alive today because a very, very conscientious researcher had read my Pap and decided to break the code and find me.”

Joan Rachlin found out she had cancer 27 years ago, purely by accident. There were no guidelines at the time for telling her.

Courtesy of Joan Rachlin

Joan Rachlin found out she had cancer 27 years ago, purely by accident. There were no guidelines at the time for telling her.

There were no guidelines — the researcher just went rogue. More checks showed Rachlin did indeed have cancer, but it was early stage and surgery took care of it.

Today whole industries are building up around the possibility that a test will find a medical problem that was just about to kill you. The latest entry — whole genome tests that promise to detail your medical future in a drop of spit.

But it’s starting to become clear that not all these findings are lifesaving, and some can be downright harmful. Take the case of the elderly woman whose chest lung X-ray showed what looked like lung tumors. She had a biopsy done — a tricky procedure that involves poking a long needle through the chest wall, or sending a bronchoscope down into the delicate lungs. Her lung collapsed and she died. The tumor, it turned out, was harmless. Were it not for the scan, she would have still been alive.

Her case is outlined in a report issued last month by the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues.

As more and more tests become available and standard, from MRIs to CT scans, to genetic tests and ultrasounds, these issues will come up more often. There’s even a name for these often harmless tumors that get discovered — they’re called incidentalomas.

For instance, 10 percent of brain scans and more than 30 percent of abdominal CT scans turn up something that doctors weren’t looking for and that may need more tests, says Dr. Stephen Hauser, who heads the neurology department at the University of California, San Francisco and who helped lead the Bioethics Commission panel in its report on the issue.

Source: Nmc news