Getting your tonsils out: It’s a rite of passage for hundreds of thousands of U.S. kids every year.

Yet a study released Monday shows hospitals vary greatly in just how they handle this common procedure. And kids fare differently depending on which hospital they go to. At the best hospitals, just three percent of kids came back for complications like bleeding. But at others, close to 13 percent did.

It is the latest in a series of studies showing that Americans get vastly different care depending on where they live.

It’s not clear why, but the researchers who did the study say it will be worth looking into so that all hospitals can make sure children recover well from the operations. New guidelines issued in 2011 may help get all hospitals and pediatric surgeons on the same page, other experts said.

It’s something in the public eye with the case of 13-year-old Jahi McMath, who died after complications from a complex tonsil operation in December at Children’s Hospital in Oakland, Calif. McMath had her tonsils out, along with her adenoids and parts of her upper throat to try and improve serious sleep apnea.

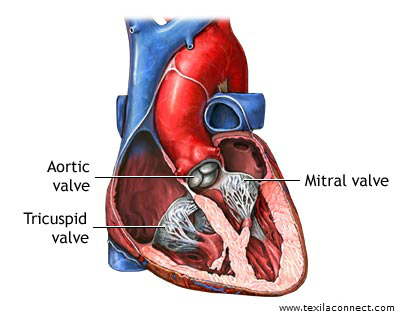

She started bleeding profusely and went into cardiac arrest shortly after. Doctors said Jahi was brain dead, but the family sued first to keep their daughter on life support, then to remove the body to a facility where her body will be kept on life support.

McMath’s operation was a complicated one. Researchers who did the study published Monday in the journal Pediatrics looked at simpler cases.

Dr. Sanjay Mahant of the University of Toronto and the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, and colleagues across the United States, looked at the records of nearly 140,000 children who got simple, uncomplicated tonsillectomies at 36 children’s hospitals between 2004 and 2010. All got same-day operations and were sent home on the day of their procedure.

Over that time, about 8 percent had to go back to the hospital within a month, usually for bleeding.

The researchers also looked at the use of two common drug types — dexamethasone, which can reduce complications such as nausea, and antibiotics.

New guidelines issued in 2011 advise giving dexamethasone to children before the operation, and they recommend against giving any antibiotics.

In the study before the guidelines came out, 76 percent of the children got dexamethasone, and at some hospitals almost none did. And 16 percent of children got antibiotics, although at some hospitals 90 percent of patients did.

“More than 500,000 tonsillectomies are performed each year in children in the United States, most commonly for sleep-disordered breathing and recurrent throat infections,” the researchers wrote. There shouldn’t be such variation from one hospital to another, they said.

It’s one of the reasons the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) issued practice guidelines based on what the studies show – that giving kids dexamethasone before the operation helps, and that giving them antibiotics doesn’t.

“These recommendations are based on evidence gathered from trials over the past two decades, which showed that dexamethasone, administered on the day of surgery, reduces postoperative nausea, vomiting, and pain, whereas perioperative antibiotics do not reduce postoperative bleeding,” Mahant’s team wrote.

Tonsillectomies are mostly done now to help sleep disorders. “There is an increased focus on sleep health in children,” said said Dr. Emily Boss, an assistant professor with the Johns Hopkins University Department of Otolaryngology and a member of the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality.

Children can start bleeding as the scab formed after the operation naturally sloughs off, Boss added. “It’s one of the well-known complications,” she said. “It’s hard to predict who will have bleeding and who will not.”

It’s almost certainly nothing the child or parents are doing, Boss added. She said there’s no evidence to support common beliefs about what causes it, such as that eating scratchy food breaks off the clot.

Children do prefer soft, cool foods because their throats are sore, she added. And yes, popsicles or ice cream are not just allowed, but recommended.

“I think this study will force the issue of practicing according to evidence-based guidelines,” Boss said.

There were not any established guidelines before, Boss told NBC News. “People practiced based on their own experiences for a long period of time,” she said.

Other medical organizations are also starting to stress clear practice guidelines. And the Obama administration is also encouraging them, to help make care more consistent and to help lower costs.

A study published by the Dartmouth Atlas project last October found variation in all sorts of treatments. For example, in San Angelo, Texas, 91 percent of heart attack patients filled a prescription for a beta-blocker drug to lower blood pressure in 2008 or 2009, the study found. But in Salem, Ore., just 62.5 percent did. For a statin drug to lower cholesterol, the rates ranged from 91 percent of patients in Ogden, Utah to 44 percent in Abilene, Tex.

Prices vary, also, often with little apparent rhyme or reason. Last week another study found that the hospital charges in California for giving birth can vary from $3,000 to $37,000 – and that’s for a simple, uncomplicated delivery.

In May, the federal government said it would start publishing data on hospital charges. Their first numbers confirmed what health reform advocates complained about for years: The charges vary enormously, and for seemingly unclear reasons.

Source: nbc news

&cropxunits=635&cropyunits=681&format=jpg&quality=90)